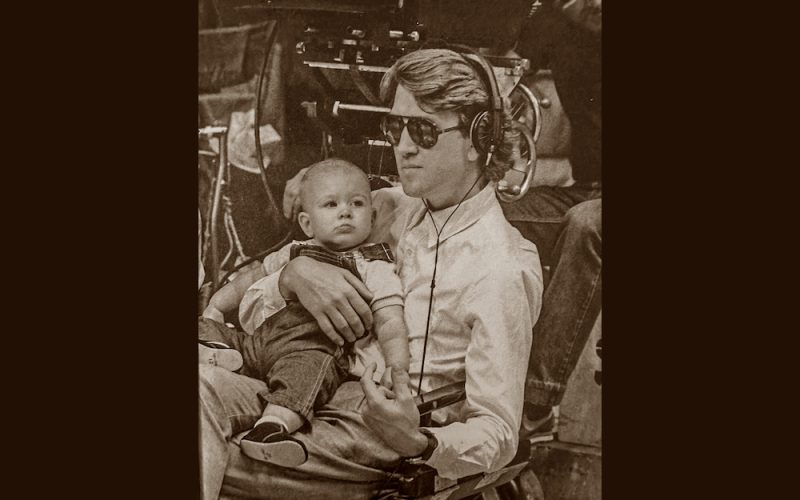

Director David Lynch’s infant son wasn’t mentioned in any of the dozens of sources for the chapter I wrote on his fateful Dune (1984) film. I only stumbled across this info in one of the last sources I looked at for a quick cross-check of a different fact. This source was Lynch’s autobiography, Room to Dream (2018), coauthored with Kristine McKenna and full of interviews with people in Lynch’s life (read more about it in Vice‘s article Women Are the Most Surprising Part of David Lynch’s New Memoir).

It was here that I read about his then-spouse Mary Fisk giving birth to their son, Austin, in September 1982, and having the support of Lynch in the delivery room, only to become a virtual single parent when Lynch then went down to Mexico to film Dune. She said it was a hard place to take a newborn because she was breastfeeding, but she still visited a few times and Lynch was able to watch Austin take his first steps in a hotel room. Fisk also made the decision to move from Los Angeles to Virginia to be nearer family. This unsettled Lynch’s daughter from his first marriage, Jennifer, who remained in LA. Jennifer was still able to see her father when he was in LA working on the film, but she knew he now had a young family and a home base across the country from her.

It was here that I read about his then-spouse Mary Fisk giving birth to their son, Austin, in September 1982, and having the support of Lynch in the delivery room, only to become a virtual single parent when Lynch then went down to Mexico to film Dune. She said it was a hard place to take a newborn because she was breastfeeding, but she still visited a few times and Lynch was able to watch Austin take his first steps in a hotel room. Fisk also made the decision to move from Los Angeles to Virginia to be nearer family. This unsettled Lynch’s daughter from his first marriage, Jennifer, who remained in LA. Jennifer was still able to see her father when he was in LA working on the film, but she knew he now had a young family and a home base across the country from her.

This book also revealed Lynch’s tendency toward getting involved with a variety of women, including during his time working on Dune. An interview with Eve Brandstein includes details about their couple-year affair after she met Lynch in 1983 while visiting a friend in Mexico who worked on the casting for Dune. According to Fisk, Lynch told her he was worried about their marriage, and she noticed when visiting him in Mexico that girls were all over him at parties. She believed that the usually straight-laced Lynch had been influenced by party-girl and producer Raffaella de Laurentiis and others to go wild and start partying. Fisk and Lynch ended up divorcing in 1987.

All of this to say, Lynch had significant additional factors and stressors in his life during the time he was also taking on his first big-budget Hollywood movie. Separated from his new baby boy and spouse in the US, and falling into a new lifestyle full of temptations, he likely had less capacity than normal to deal with the numerous challenges during production and editing.

I probably shouldn’t be surprised that this part of Lynch’s life as a young director has been left out of the historical record of the making of Dune. The personal lives of men are often assumed to be detached from their professional lives, whereas women find it more difficult to separate the two when they are the ones bearing children and managing their household. Also, since this book wasn’t published until 2018, it’s hard to know how much of this information would have been available for writers and reporters even if they had wanted to explore more of the personal factors in Lynch’s experience. Yet even Max Evry’s new book A Masterpiece in Disarray: David Lynch’s Dune. An Oral History (2023)—full of interviews with cast and crew—avoided this family life aspect. Only Alicia Witt (who played Alia Atreides) mentioned in her interview that Lynch had had two children by the time of filming and was great with kids, and she remembered because she had been a young child actor at the time.

To me, the fact that Lynch had a new baby that he would have been thinking of, even if he rarely had the chance to see him, and a spouse trying to find better support for herself and moving their family home, is important contextual information for the making of the film Dune. So for my part, I’m going to do my bit to remedy this and note it in the background section in my forthcoming book on the screen adaptations of Dune. It should at least be acknowledged as part of the larger discussion about why Lynch found this film such a challenge and why its critical failure may have stung even harder.