Despite stated intentions to focus on women and expand their roles, the new Dune film adaptations disappointingly fall back on stereotypes for the Bene Gesserit and undermine the political, religious, and maternal agency of Jessica in particular.

Cast and Crew Intentions

Director Denis Villeneuve has discussed in numerous interviews that he wanted to focus on the women in his adaptation. Before Dune: Part One, he said: “For me, it was important to bring more femininity to the story. I am fascinated by the relationship of femininity and power, the place of women in society…. [Lady Jessica]’s a fascinating character, one of the most influential and most interesting in the novel.” (Denis Villeneuve Gave ‘Dune’ Writer Mandatory Goal: Focus on the Women Characters)

Before Dune: Part Two, he reiterated, “I always have been, since I was born as a filmmaker, concerned, inspired, and sensitive about the female condition and women’s relationship with power…. I want the movie to be an adaptation about the Bene Gesserit. I want the Bene Gesserit to be at the center of the epicenter of this adaptation. It’s one of the things I feel is the most accurate with our time.” (Denis Villeneuve Explains Why Women Are ‘the Epicenter’ of His Dune Universe)

Other cast and crew have discussed their belief that the portrayal of women in Frank Herbert’s book was outdated and required modernization. Co-writer Jon Spaihts noted, “We also felt there was room to look for [even] more female participation, because there are ways in which Dune was very progressive for its time — but its time was the ’60s.” (‘Dune’ team on splitting up the book, expanding the female roles and ‘Part Two’ planning) Playing Jessica on screen, actor Rebecca Ferguson commented that “this character was quite suppressed by her ‘owner’… I think it was really important for Denis to focus on Lady Jessica and layering the character with strengths and vulnerabilities to bring her up to the equality we need to portray women today.” (SCI FI Magazine, Fall 2021)

My Interest

I became interested in looking at how the new films would adapt the women in Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel Dune (1965), particularly the Bene Gesserit, to the screen, and what changes they would make to the source material to try to modernize these characters. To me, these women were already incredible on the page.

In the scholarly realm, I’ve studied and written about the Bene Gesserit extensively through the framework of how much agency women have in the novel, concluding that they have a high degree of bodily control as well as political, religious, and maternal influence to be able to make decisions and accomplish their goals. (For more on the Bene Gesserit, see my essay Frank Herbert, the Bene Gesserit, and the Complexity of Women in the World of Dune at Tor/Reactor; my series of blogs on Who Are the Bene Gesserit; or my book Women’s Agency in the Dune Universe).

Though grounded in archetypes and real-world religious orders, they are crafted as characters with complexity who face a thought-provoking tension between following their individual desires and those of the larger collective they are part of. Their voices also take up a significant amount of space in the story, whether through Irulan’s writings or Jessica’s thoughts and actions as a major character alongside her son, Paul. Given this, I find it curious that such characters would need to be changed to appeal to modern audiences.

Bene Gesserit in Dune: Part One

In my new book Adaptations of Dune, I discuss how the Bene Gesserit women in Dune: Part One sometimes resemble their book counterparts. For example, they have linkages with the Catholic Church through their black dresses and veils, and their hats are modeled off of those of Greek Orthodox archbishops. The gom jabbar scene is set up like a confessional and Paul has to pass this test kneeling before a veiled Reverend Mother Mohiam.

In my new book Adaptations of Dune, I discuss how the Bene Gesserit women in Dune: Part One sometimes resemble their book counterparts. For example, they have linkages with the Catholic Church through their black dresses and veils, and their hats are modeled off of those of Greek Orthodox archbishops. The gom jabbar scene is set up like a confessional and Paul has to pass this test kneeling before a veiled Reverend Mother Mohiam.

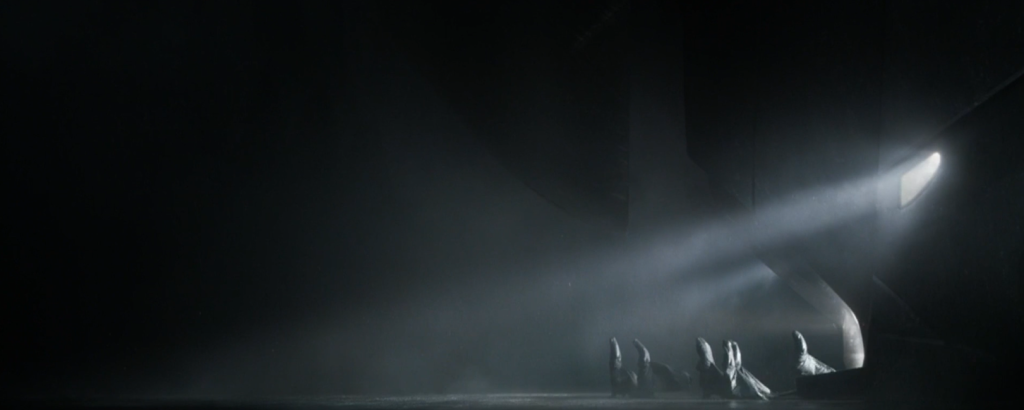

But the Bene Gesserit are also shown to be overly cold and menacing, emphasized through the rain and the wind as well as the soundtrack. There isn’t an opportunity for Mohiam to counsel Paul or comfort Jessica before their move to Arrakis, as Mohiam does in the book. Meanwhile, other Bene Gesserit huddle silently in groups with obscured faces, seemingly uncaring figures. These depictions in the film foster a sense of antagonism between women, rather than one of a group of women bonded together due to their shared schooling and working together to strengthen humanity in their vision for the universe.

The biggest change was to make Mohiam complicit in the Baron Harkonnen’s plot and lose a sense of neutrality or political subtlety for the Bene Gesserit order. Nor does the Baron seem afraid of Mohiam or her Truthsayer abilities, which in the book is a signal of how influential the Bene Gesserit are at the highest level of the Imperium.

Jessica, meanwhile, is a mixed bag. She maintains her skill in combat and reproductive control from the book and educates her son. But she appears overly emotional and ignorant for a highly trained woman, and even untrustworthy when Leto accuses her of walking in shadows. She engages in more violence and uses the Voice more than in the book, reflecting an attempt to make women appear more stereotypically strong. Yet she lets Stilgar go from her grip and leaves herself vulnerable when she and Paul encounter the Fremen, and desperately asks for help escaping offworld, rather than stepping into the role of acting as a regent for Paul and paving the way for their safety. Paul openly disagrees with her plan to escape and says they will stay with the Fremen, meaing the film ends with her and Paul not on the same page.

Bene Gesserit in Dune: Part Two

I plan to cover the adaptation of Dune: Part Two in full detail in my next book, but I couldn’t wait that long to write down my initial thoughts about what I find to be a disappointing portrayal of the Bene Gesserit. Dune: Part Two takes even greater steps away from the source material, and leans so hard into the portrayal of the Bene Gesserit as manipulative schemers that it strips them of their three-dimensionality and many aspects of their agency. Its radical changes are more disempowering than not, particularly for Jessica.

Jessica possesses only a fraction of her agency as a mother, a regent, and a religious leader in this film. In an opening scene, she and Paul work together to kill Harkonnens, though she still chastises him about his behavior. But then the film quickly moves to drive a wedge between them, rather than showing her acting as a regent and trusted advisor to him as he matures and embraces a leadership role among the Fremen. Paul appears as a reluctant hero who resists embracing the messianic role prepared by the Bene Gesserit. This places Jessica in the role of an antagonist, pressuring Paul to use religion as a tool to gain power against his wishes.

Instead of calculating that the Water of Life ceremony is a dangerous but necessary chance to solidify their place among the Fremen, she seems forced into it by Stilgar and openly begrudges it. The scene is not like the one in the book—an intimate look at an old woman leader passing on her consciousness to a mother and her female fetus, presided over by Chani as the Sayaddina-in-waiting in case Jessica should fail. Instead, the film shows it to be something mysterious and stressful happening off to the side, with an unnamed Fremen Reverend Mother having to use the Voice to force Jessica to drink, and a doubting Chani looking disgusted at this aspect of her own culture.

Though Jessica survives and is exoticized through marks on her face and elaborate costumes, there is not a strong sense that she is now the key religious leader among the Fremen of Sietch Tabr, someone who is consulted in major decisions and sits atop their religious hierarchy. The presence of Chani’s group of Fremen in particular—who offer a strong dose of postmodern skepticism about anything religious or mystical—casts doubt upon the significance of Jessica surviving this ceremony, which is such a pivotal part of Fremen culture in the book. The ceremony starts her down the path of being a strange woman who talks to her fetus, now awakened and apparently communicating with her. Paul continually asks his mother how the fetus is, drawing attention to her pregnancy, even as he distances himself as a son.

In fact, once she begins conversing with her fetus, Jessica becomes further isolated from those around her, a witch-like figure conspiring with hidden beings to conjure the outcome she wants for her reluctant son. Instead of the ancestral memories helping her connect with the Fremen culture, they seem to haunt her and further drive her to spread the cult of Paul. The constant doubting on the part of some Fremen only adds to the sense that she is a suspicious figure, rather than one being folded into the community. She does not help train the Fremen in the weirding way of combat as she does in the book, even though Stilgar comments on her being a “weirding woman and a fighter” at the end of Part One. Her main role becomes to spread myths among the unbelievers as her increasingly distant son tries to push against his training and prepared path.

This film makes it even more apparent that Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth was used as a source of inspiration for Lady Jessica on screen, a curious choice for a reference character (Rebecca Ferguson Talks Dune, Lady Jessica, and the Epic Scale of Denis Villeneuve’s Films). Lady Macbeth is power-hungry and able to convince her spouse to do something he is reluctant to do: betray his king and seize the throne. When Jessica acts as a force against what Paul says he wants, against what Chani wants for the Fremen, she takes on a similar near-villainous persona.

But this is not how Jessica is crafted in the book. She has a strong hand in guiding and shaping Paul, and he trusts her and wants her at his side advising him. This is a special aspect of the story, that the male hero takes his journey with his mother, who acted out of pride to bear and train the long-awaited Kwisatz Haderach herself, rather than patiently waiting for the right time in the breeding program. The mother-son bond is a key component of the book. They don’t always agree, but they work together to find their way back to their seat of rule. The film undercuts this relationship and instead reduces Jessica to a schemer increasingly alienated from her son, whispering to her fetus.

Dune: Part Two briefly shoehorns Lady Margot Fenring in to perform only one of her roles from the book, that of a seductress who can maintain the Harkonnen bloodline for the Bene Gesserit breeding program. Princess Irulan appears too, under the thumb of Mohiam, who makes the Bene Gesserit seem vengeful in her late reveal about the order’s involvement in the downfall of House Atreides, a substantive deviation from the book. There is little to no room for enough character development to go beyond the stereotype of women as ‘femme fatales’ who manipulate and trap the men around them. And the lack of the Guild’s presence at the end prevents the audience from seeing this other major faction and how it plays similar games of politics. But there is time to show a vision of a grown-up Alia telling Paul she loves him, and to show Jessica and Mohiam communicating telepathically, neither of which is from the book.

Closing Thoughts

In the book Dune, author Frank Herbert crafted the Bene Gesserit as a way of showing and critiquing the power of religious ideas and the idea that humanity could or should be tightly controlled. In the process of developing this order of women, he equipped them with an incredible amount of control over their bodies and the skills and astuteness to wield power and influence through various channels. Likely modeled off of Herbert’s beloved spouse and writing partner Beverly, the character of Jessica remains one of the most fully developed female characters in science fiction, as well as being a three-dimensional mother figure.

Meanwhile, Denis Villeneuve’s film adaptations, seemingly in an attempt to be progressive, de-emphasize women’s love and concern for men and turn Jessica into a more violent character who loses the respect of her son and is left to her own devices. (The change to Chani is another story altogether…) The films emphasize the Bene Gesserit’s scheming and manipulation, which threatens to solidify the audience’s view of them as primarily villainous and reinforce problematic stereotypes about powerful women.