A good proportion of teens seem interested in learning more about Frank Herbert’s Dune, especially younger ones in the prime demographic for encountering this science fiction classic. Oh, to be discovering and reading Dune for the first time – that experience certainly shaped my life!

Following on from my recent presentations on the novel Dune to several junior high/high school classes (thanks to those who responded to my post about what to cover :), I wanted to report back on what teens had questions about and what piqued their attention the most.

There were some basic questions like how long have you been studying Dune (a lot!) and do you write about other topics (yes, but you tend to stick with a niche in academia because you know a lot about that subject). When I talked about the real-world spice trade and high value of spices like cinnamon, they were surprised and wondered why they would be so valuable. It is quite difficult to imagine nowadays, when these are ordinary and affordable at the grocery store.

One thing that stood out to me was how they didn’t realize authors could bring so much about social issues into their work. I definitely emphasize the historical context and issues of the time whenever I discuss Dune, so I hope this was a nugget of information they can apply to other authors they study, to look into how authors might incorporate social issues into their characters and stories. The 20th century might seem far away from today, but we are still dealing with a lot of those same issues, just in different forms.

There were also more specific questions based on elements they saw in the new films, Dune: Part One and Dune: Part Two such as Why are there sandworms? What are they based on? Other questions revealed that they didn’t understand a lot about what was going on in the films. They wondered, What was the blue liquid? If there’s no advanced technology, how do they move between planets? So little was explained on screen. I hope this leads them to read the book to find out more, although Herbert often has few descriptions and lets you use your imagination to fill in details.

Other aspects that engaged their attention were when I asked them to consider things like why a writer would put a map in a book, why Herbert might have named his main character Paul, and how one of the inspirations for the book was the scientific experiment about using grasses rather than walls to stop sand dunes in Oregon. World-building is definitely still one of my favorite areas of study when it comes to Dune, and it seems an accessible entry point into thoughtfully discussing the story, whether or not you’ve read the book.

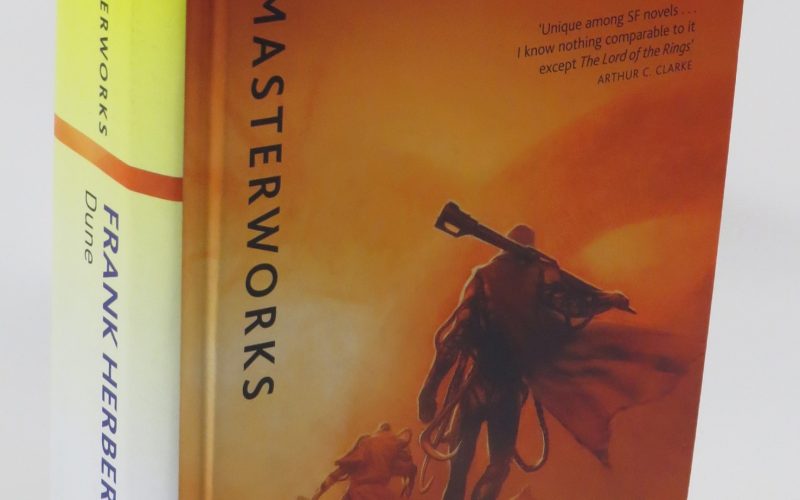

It was a nice opportunity to present to a younger audience, and one student immediately requested the library’s copy of Dune to read, so I convinced at least one to give it a try! I was pleased to see that the library had copies of my own books available too in case any brave young person wants to go for deeper scholarly analysis. Television and film are great inventions, but there’s still something special about the written word. I hope young people continue to discover this classic and find something that speaks to them in their time and place.