The parallels between the life of Gertrude Bell, British archaeologist and writer, and the character Lady Jessica in Frank Herbert’s Dune make for an interesting study of how women can successfully carry themselves in unfamiliar territory and exert influence.

Although T.E. Lawrence (1888 – 1935) is more well-known, in no small part due to the popular movie based on his time in the Middle East (Lawrence of Arabia (1962)), Gertrude Bell (1868 – 1926) was a significant Western figure in the Middle East in the 20th century and arguably more extraordinary in terms of her influence. Known as a queen or daughter of the desert, Bell was a woman who dared to travel across Arabia and managed to secure the admiration and respect of many of the locals as well as shape the future of Middle Eastern politics.

In Dune, a science fiction book with influences from the Middle East, the protagonist Paul Atreides has received the bulk of critical attention and has been noted to be a type of Lawrence of Arabia figure due to the many similarities in their characters (see my essay Lawrence of Arabia, Paul Atreides, and the Roots of Frank Herbert’s Dune). Yet having studied Bell’s life in more detail, I have found interesting parallels between her and Jessica. In this article, I focus on some of the commonalities between these two women that emphasize how they were able to navigate unfamiliar and sometimes dangerous territory and use their education and skills to influence those around them.

Who was Gertrude Bell?

In her day, Bell was the most famous British traveller. [1] The first woman to earn a first-class degree in modern history at Oxford, she became an archaeologist, diplomatist, translator, and writer with a focus on the Middle East who authored many articles and seven books, the most well-known being The Desert and the Sown (1907). [2] [3] [4] She spent almost a decade between 1905 and 1914 on multiple journeys and archaeological expeditions in Syria, Arabia, Turkey, and Asia Minor. [5] The Arabs called her a “daughter of the desert”, and she played a significant role in the formation of the state of Iraq. [3] [6] After her travels she helped create the Baghdad Archaeological Museum [3]. Her attachment to the area was such that she was actually buried in Iraq. (See the Gertrude Bell Archive and Gertrude Bell research site run by Newcastle University for more information on Bell’s life.)

Georgina Howell’s book Queen of the Desert: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell (turned into a film starring Nicole Kidman in 2015) paints a vivid picture of this adventurous woman who learned several languages and insisted on being taken seriously in a man’s world. Bell spoke much better Arabic than Lawrence and developed a deep love of the Middle East throughout her life, such that she worked toward its peoples not being subsumed under the wishes of the British Empire.

She was a woman who enjoyed challenges, exploration, and learning. Howell asks the question many who learn about Bell have wondered: “Why did this wealthy young woman spend years of her prime learning some of the most difficult languages in the world and make great efforts in order to pit herself against truly appalling conditions and great dangers and go to places so obscure that they did not figure on any contemporary map?” [1]

Because she was curious, and traveling in the desert far from home offered a variety of ways to challenge herself, explore, and learn, away from the pressures of high society. For her, “there were languages to perfect, customs to learn, new kinds of human being to plumb, archaeology and history to explore, the techniques of surveying and navigation, photography and cartography to acquire. There was the risky business of staying alive and reaching her goal; and the intoxication of asserting her own identity far from the world” where she was known as the daughter of Hugh Bell. [1]

Similarities between Bell and Jessica

There are several similarities between the real-life Bell and the fictional Jessica. Here I present a brief overview based on excerpts from Bell’s own writings and Howell’s characterization of Bell in her biography.

Privilege

Both Bell and Jessica were women of privilege. Bell was the daughter of a wealthy man with business dealings in England who paid her a stipend for her travel and living costs. She did not need to work for a living, although she did end up doing a significant amount of work during her time away. She was accustomed to a certain lifestyle, and this showed in how she traveled in style. Indeed, her nickname Queen of the Desert reflected how she traveled with all of her various luxuries:

[H]er mode of travelling, from 1909, was nothing short of majestic. […] She did not forget the Druze Yahya Beg’s questioning the local villagers, ‘Have you seen a queen travelling?’ She packed couture evening dresses, lawn blouses and linen riding skirts, cotton shirts and fur coats, lawn blouses and linen riding skirts, cotton shirts and fur coats, sweaters and scarves, canvas and leather boots. Beneath layers of lacy petticoats she hid guns, cameras and film, and wrapped up many pairs of binoculars and pistols as gifts for the more important sheiks. She carried hats, veils, parasols, lavender soap, Egyptian cigarettes in a silver case, insect powder, maps, books, a Wedgwood dinner service, silver candlesticks and hairbrushes, crystal glasses, linen and blankets, folding tables and a comfortable chair – as well as her travelling canvas bed and bath. [1]

But this type of travel was not merely about comfort. Bell did like “to travel in style, but she knew that the sheikhs would judge her status by her possessions and her gifts, and treat her accordingly.” [1] Her status and ability to bring gifts helped insulate her from some of the dangers of traveling as a woman with a very small group.

Although Jessica’s upbringing was more humble at the Bene Gesserit school, and as a child she was kept ignorant about who her parents were, her role as the bound concubine of the nobleman Duke Leto Atreides gave her high status in the world of Dune. She was called Lady and treated as such by members of the Atreides household, with access to the fineries of the nobility. She also did not need to work in a traditional occupation, but still did operate as Leto’s secretary for his busines dealings.

These women’s privilege was also reflected in how they carried themselves. They moved with a feminine grace expected of women in their positions, and with a stateliness that indicated they expected others to accept their commands. For example, at one point, it was noticed by Paul “how [Jessica] failed to blend with the Fremen even though her garb was identical. The way she moved – such a sense of power and grace”. [7]

Travel

Yet each woman, for different reasons, left the comfort of her family home for a new, unfamiliar place. Bell chose to leave England and travel throughout the Middle East. Her journeys took her across desert environments in extreme weather conditions, and into hostile and dangerous territories. In her letters and writings, she described “journeying alone in the early 1900s, surrounded only by Arab men, speaking almost no English, sleeping in tents, riding camel or horse through dangerous regions, risking robbery and even death”. [4] Many times she found the experience liberating though – an adventure that was always changing, requiring her to stay on her toes and constantly learn and adapt.

Jessica traveled with her family from the Atreides’ homeworld of Caladan to the desert planet of Arrakis, or Dune, which also had several similarities to Iraq, including a punishing heat and various threats. Although Bell wanted to leave while Jessica did not have much if any choice, it still required courage on both women’s part to travel into a foreign environment with challenges and potentially deadly situations. This was especially the case for Jessica after Leto’s death, when she and Paul had to flee from their Harkonnen captors and make their way among the Fremen. Jessica then became a single woman like Bell, attempting to not only survive but thrive in a potentially hostile environment, and with her son to consider as well.

Both women managed to survive dangerous encounters and relied on themselves to some extent for defense. As the “first woman who had ever been to the Safeh, that wild territory continually swept at the time by tribal raids from both north and south”, Bell quickly learned to “ride fully armed” for protection. [1] Jessica used her Bene Gesserit combat skills and the Voice to protect herself at various times.

Influence

Their high degree of perceptiveness served these women well in a new world. By relying on their communication skills and ability to understand and adapt to the local cultures, they were able to avoid conflict and gain people’s trust. They then could leverage their position to become women of influence. Being educated and knowing multiple languages also assisted them in their dealings with others.

Bell spoke French, Italian, Persian, and German, and understood some Hebrew, and she learned Turkish and Arabic as well, though Turkish was “the only language she did not retain”. [1] She gradually learned how to forge friendships and obtained the assistance of various tribespeople she encountered. For instance, one group of Bedouins of the Beni Sakhr tribe who had previously caused her trouble, later came to accept her: “‘Mashallah! Bint Arab,’ they declared – ‘As God has willed: a daughter of the desert’”. [1] On her travels, Bell would ride “straight to the tent of any sheikh in the vicinity, greeting him in fluent Arabic and with all conventional deferences. She paid for the usual rafiq, as any male traveller would have done, but as a woman she had, for her very life, to convince the sheikh that she was his equal”. [1] Through gift-giving, communication, and presentation, Bell could represent herself “with her regal bearing and assertive self-confidence protecting her like a suit of armour”. [1] She could show a sheikh that she was not his enemy and “might even, with her connections, be his ally”. [1] Riding in the saddle as men did and bringing news and gossip, she was not like other women and used this to her advantage to access places that women of the harem could not. [1]

Bell also entered the world of men on the British side. Being fluent in Arabic as she travelled enabled her to gain a valuable overview of the Arab system of government and the importance of family and tribe relationships. [1] This came in handy when she began work in Cairo as the “first woman officer in the history of British military intelligence”. [1] She “exercised influence by delivering first-hand knowledge and opinions based on that knowledge. At home and abroad, she conferred with the greatest men of her day”. [1] In fact, Bell was an important influence on her friend Lawrence and his work: “it was Gertrude’s advice and knowledge of desert affiliations that guided him. He admitted that he owed to her much of the information that had helped him to rally the tribes in the desert at a critical moment during the Arab Revolt”. [1] [4]

Jessica, too, had to bridge the gap between multiple worlds through language as well as quick thinking and good diplomatic skills. Her Bene Gesserit education taught her to speak the common tongue Galach as well as “the Bhotani Jib and the Chakobsa, all the hunting languages”. [7] After her and Paul’s flight into the desert, she was faced with the task of convincing the skeptical Fremen tribe they encountered that she had value. She proved her worth by showing her fighting skills, then by seeming to have access to secret knowledge an outsider wouldn’t be expected to know. She drew on her memory of a word on a map she had seen some time ago, Sietch Tabr, and the Fremen were astonished when she spoke its name. This is similar to how Bell soaked up information on her travels about various tribes and customs and then used it to enhance her standing.

To further guarantee her and Paul’s safety among the Fremen, Jessica undertook the dangerous Water of Life ceremony to become a Reverend Mother. After absorbing the dying Reverend Mother Ramallo’s memories, she was empowered with the memories of many Fremen ancestors. Her local knowledge and understanding thus multiplied, further solidifying her position, and she gradually built up her own network of spies to keep herself informed. She also acted as a trusted and respected advisor to both Paul and the Fremen leaders, just as Bell did among members of British intelligence.

Loyalties

Yet both women still had a foot in their home culture and found themselves having to balance exploitation and genuine care for the people they lived with. Overall, Bell respected the peoples she met and acknowledged their rich history:

Race, culture, art, religion, pick them up at any point you please down the long course of history, and you shall find them to be essentially Asiatic … Some day I hope the East will be strong again and develop its own civilization, not imitate ours, and then perhaps it will teach us a few things we once learnt from it and have now forgotten, to our great loss. [1]

Bell’s bond to the Middle East showed through in her writing and in her work to foster healthy cross-cultural relationships, and later to preserve Middle Eastern archaeological artifacts in the Baghdad Archaeological Museum. In 1917, she wrote: “I have grown to love this land, its sights and its sounds. I never weary of the East, just as I never feel it to be alien. I cannot feel exiled here; it is a second native country”. [1]

Like T.E. Lawrence, she admired the nomadic Bedouin people and “their powerful mystique” and “independence, mobility and resilience”, though both writers also had Orientalizing tendencies stemming from their British worldview. [1] Both faced conflicted decisions regarding the British influence in the Middle East and its agenda for the region, which did not necessarily match the promises the British made to the Arabs. They felt the dilemma of encouraging the Arabs to revolt against the Turks to help the British win the war. [1]

As for Jessica, she knew she had been manipulating the Fremen from the beginning through her use of the propaganda of the Missionaria Protectiva. She wanted to see her son gain power and reclaim his father’s ducal position. However, she also adopted the Fremen way of life and key aspects of their thinking. She adapted to the water discipline and took on the role of a significant religious leader as a Reverend Mother. Her experience living among the Fremen for years molded her into a different person, someone whose identity became a hybrid or fusion of two cultures. [8]

The many similarities between Bell and Jessica point to their characterization as strong, capable women who could handle themselves in challenging environments. They leveraged their privilege, education, and intelligence to find safe passage in a foreign desert world and interact productively with people with different customs and worldviews, though they also faced tensions in their loyalties. Both were unescapably shaped by their experiences and demonstrated women’s ability to carry themselves in unfamiliar territory to become influential and respected figures in the halls of power.

References:

[1] Howell, Georgina. Queen of the Desert: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell. Pan MacMillan, 2015. Pages 102, 122, 124, 127-129, 130-131, 180, 194, 196-197, 221, 257, 267, 297, 370.

[2] Cannon, John, and Robert Crowcroft. “Bell, Gertrude.” A Dictionary of British History. Oxford University Press, 2015.

[3] Taddeo, Julie Anne. “Bell, Gertrude.” The Oxford Encyclopedia Women in World History. Oxford University Press, 2008.

[4] Wallach, Janet. Desert Queen: the Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell: Adventurer, Adviser to Kings, Ally of Lawrence of Arabia. Doubleday, 1996. Pages xiii, xxiv, xxv.

[5] Gilmartin, Patricia. “Bell, Gertrude.” The Oxford Companion to World Exploration. Oxford University Press, 2007.

[6] “Bell, Gertrude.” The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature, edited by Dinah Birch and Katy Hooper, Oxford University Press, 2013.

[7] Herbert, Frank. Dune. 1965. Reprint Berkley Books, 1984. Pages 53, 289.

[8] Kennedy, Kara. “Epic World-Building: Names and Cultures in Dune.” Names, vol. 64, no. 2, 2016, pp. 99-108. doi: 10.1080/00277738.2016.1159450

Image Credits:

- Public domain – Gertrude Bell with King Faisal (second from right) and others at a picnic, 1922

- Public domain – Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence at the Cairo Conference, 1921

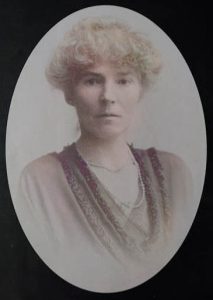

- Public domain – Gertrude Bell portrait, 1921

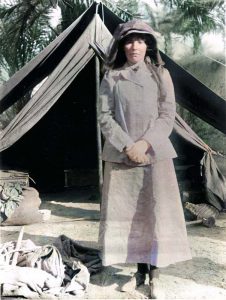

- Public domain – Gertrude Bell in Iraq, April 1909

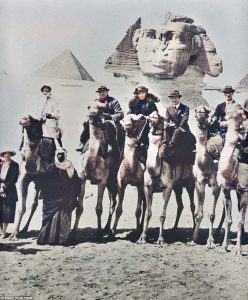

- Public domain – Gertrude Bell with Winston and Clementine Churchill and T.E. Lawrence at the Pyramids, 1921

- CC-BY-SA (colorized) – Gertrude Bell with Winston Churchill, T.E. Lawrence, and others at the Cairo Conference, March 1921

For more photographs, see Newcastle University’s Gertrude Bell Archive and Gertrude Bell research site.