The Bene Gesserit can control other people just by using their voice in Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel Dune (1965). They can also determine whether someone is telling the truth. These techniques are based on humans’ ability to modify their language and tone when they communicate. This article explores the Bene Gesserit’s skills in the Voice and Truthsaying as the fifth in a multi-part series on their abilities. (See part 1, real-world influences; part 2, nerve and muscle control; part 3, schooling in espionage and politics; and part 4, perception and memory.)

The Voice is one of the few skills of the Bene Gesserit that Herbert specifically commented on. In an interview, Herbert explained that we already have the ability to control other people with our words and actually do it a lot, if we stop to think about it. He said:

I’ll give you an example. I’m going to describe a man to you, and I’m going to give you the task of controlling him by voice after I’ve described him. This is a man who was in World War I as a sergeant, came home to his small town in the midwest, married his childhood sweetheart and went into his father’s business, raised two children whom he didn’t understand. Now, on the telephone, strictly by voice, I want you to make him mad…. Simplest thing in the world! Now, I’ve drawn a gross caricature, but we’re saying that if you know the individual well enough, if you know the subtleties of his strengths and weaknesses, that merely by the way you cast your voice, by the words you select, you can control him. Now if you can do it in a gross way, obviously with refinement you can do it in a much more subtle fashion. [1]

Herbert’s work as a journalist, political speechwriter, and writer on concepts from general semantics (more on general semantics in another article) gave him insight into how powerful language is in shaping people’s ideas and reactions. His own explanation shows that he did not intend for the Voice to be a kind of supernatural mind control, but rather a skill that could be taught and practiced.

The Voice in Dune

In the Dune series, the Voice is the ability to control the behavior or influence the thoughts of others merely by using one’s own voice in a particular way. It requires first studying another person’s voice and/or mannerisms to know what the right pitch, etc. will be to control them.

As with many aspects in Dune, the Voice is not explained in detail. Herbert relies on the exchange between Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam and Paul Atreides in the opening chapter to introduce this phenomenon to us:

“Now, you come here!”

The command whipped out at him. Paul found himself obeying before he could think about it. Using the Voice on me, he thought. He stopped at her gesture, standing beside her knees. [2]

Herbert uses italicized text for two purposes here: first, to show that Mohiam is placing a special emphasis on a word, and second, to show what Paul is thinking. We need someone to tell us that she is putting more than just a regular emphasis on the word ‘you’, and it is Paul who knows it is special because he has been trained as a Bene Gesserit by his mother. But even though he identifies that Mohiam is using the Voice, at this point in his development he is still susceptible to obeying it without thinking.

Mohiam uses it a second time soon after when he tries to turn toward the gom jabbar needle at his neck: “‘Stop!’ she snapped. Using the Voice again! He swung his attention back to her face”. [2] Here her words are not italicized, but Paul’s thoughts tell us that it was indeed the Voice.

This introduction leaves us wanting to know more. What is this Voice? How does it work? If Paul knows what it is, why can’t he resist?

When the Voice is next mentioned, it is much later, when Jessica realizes why the Baron Harkonnen has assigned her a deaf guard: “The Baron knows I could use the Voice on any other man”. [2] It is not until Paul attempts to use it on another guard that we gain more information about how it works, via Jessica’s perspective:

“Remove her gag,” Paul commanded.

Jessica felt the words rolling in the air. The tone, the timbre excellent — imperative, very sharp. A slightly lower pitch would have been better, but it could still fall within this man’s spectrum. [2]

This brief description helps show us that the Voice is a special type of speech involving such aspects as:

- tone (a sound of definite pitch and vibration) [3]

- timbre (the resonance by which the ear recognizes and identifies a voiced speech sound), [4] and

- pitch (the difference in the relative vibration frequency of the human voice). [5]

The reference to the guard’s spectrum also adds information about how the Voice works, indicating that it needs to be customized to someone or else it can fail.

Although a full explanation of the Voice is not given, there is enough information for us as readers to piece together that it is an extraordinary ability, yet still one based on plausible extrapolations of the workings of the human mind and body. Herbert later gives a more obvious insight when Jessica is deciding whether to use it on Stilgar: “I have his voice and pattern registered now, Jessica thought. I could control him with a word, but he’s a strong man … worth much more to us unblunted and with full freedom of action.” [2]

By teasing out the Voice through brief examples, Herbert keeps some mystery surrounding the Bene Gesserit’s skillset and avoids a lengthy info dump. We can assume that part of Bene Gesserit training must include how to manipulate one’s voice, as well as how to carefully register the characteristics of another person and their voice. Herbert does include a definition in “The Terminology of the Imperium” but keeps it vague. There, the Voice is defined as “that combined training originated by the Bene Gesserit which permits an adept to control others merely by selected tone shadings of the voice”. [2]

The significance of the Voice is that it is a skill that the Bene Gesserit can use almost anywhere, anytime to prompt an immediate reaction to accomplish a task or protect themselves or others. It doesn’t require any equipment, and only those who are deaf or wearing ear protection can avoid its reach. As shown in the scene mentioned above where Paul commands the deaf guard’s companion, even having one person who can be influenced through the human voice is enough for the Bene Gesserit-trained to prevail. The Voice is a powerful ability that they use sparingly but effectively in their roles in the Imperium.

Truthsaying

Another one of the Bene Gesserit’s abilities in the realm of language and linguistics is Truthsaying, a term that is capitalized just like the Voice is. Truthsaying involves determining whether someone believes what they are saying, not necessarily whether what they are saying is factually true. This ability makes a Bene Gesserit woman a kind of human lie detector.

Truth Machines

In the real world, a lie detector test, or polygraph, measures physical aspects such as a person’s blood pressure, breathing rate, and electrical skin conductance, all while they are being asked yes or no questions. [6] It often is paired with close observation of the person’s appearance and behavior, including their gestures and talkativeness. Certainly the characteristics of the voice mentioned above can also be considered important features to observe.

According to Geoffrey C. Bunn’s The Truth Machine: A Social History of the Lie Detector, the origins of this instrument were bound up in changing conceptions during the 19th century of criminality, gender, shame, and the idea that the human body can manifest certain properties in the act of telling a lie. Bunn credits researcher Frances Kellor’s “Psychological and Environmental Study of Women Criminals” (1900) as containing the first example of a physiological test being used to tell whether subjects’ statements were true. Her work had accidentally sparked the idea that such a test could reveal a person’s secrets or lies. It would only be a short time before a lie detector instrument appeared in fictional magazine stories in 1909 and 1910, and was then later invented for real by various people, though origins are disputed. [6]

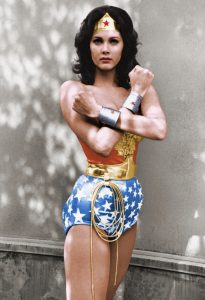

Although it was constantly criticized, the lie detector “became deeply embedded in the North American psyche” during the 20th century, between the famous Lindbergh crime in 1935 and the O.J. Simpson trial in 1995. [6] There is even a connection between one of the inventors, William Moulton Marston, and his creation of comic book heroine Wonder Woman’s magic golden lasso (now known as the Lasso of Truth), “which compelled anyone bound by it to tell the truth or obey her commands”. [7] The lie detector was used in high-profile cases, advertising, movies, and TV shows, including a Star Trek episode. [6] These helped it become a recognizable device in American culture and perpetuated the idea that it could be a truth machine, despite its flaws.

The Bene Gesserit as Truthsayers

Given Dune’s publication in the 1960s, it follows that readers would likely have been familiar with the concept of someone being able to tell whether someone were lying based on physiological ‘tells’ such as increased heart rate, sweating, etc. What makes the Bene Gesserit’s Truthsaying ability extraordinary, then, is that it requires no technology or special instruments. Although there is no explanation of how they do it, as with their other abilities, it appears to stem from their attention to detail and intricate knowledge of how the human body and voice work.

As readers, we are given the impression that all Bene Gesserit have this ability, but that there are factors that can affect their proficiency. In Reverend Mother Mohiam’s conversation with Paul at the beginning of the book, they discuss the Truthsayer drug as something that is taken to improve the ability to detect falsehood. This implies that the Bene Gesserit have a baseline level of Truthsaying that can be enhanced by a drug, later revealed to be spice.

In Dr. Yueh’s conversation with Jessica before his act of betrayal, he worries that she will unmask his treachery. He then comforts himself by telling himself that she is not as good as she could be: “Long ago, he had realized Jessica was not gifted with the full Truthsay as his Wanna had been. Still, he always used the truth with Jessica whenever possible. It was safest.” [2] At the close of the scene, we learn that Jessica had known Yueh was hiding something but didn’t want to shame him by “drag[ging] the hidden thing from him”. [2] So we are left to determine how skilled Jessica actually is given these two perspectives.

There are also official Truthsayers, with evidently some kind of certification process required to become one. In defending herself against Thufir Hawat’s accusations of treachery, Jessica notes, “A Truthsayer would solve this…but we have no Truthsayer qualified by the High Board.” [2] In the appendix, Terminology of the Imperium, Truthsayer is defined as “a Reverend Mother qualified to enter truthtrance and detect insincerity or falsehood”. [2]

One such qualified Bene Gesserit is Reverend Mother Mohiam, the Emperor’s Truthsayer. She is feared by men like Baron Harkonnen and Piter de Vries, who deliberately avoid doing anything that might cause them to have to tell a lie in front of her. In one example, this fear results in them leaving Jessica and Paul to be entrusted to two guards to be taken care of, rather than overseeing their deaths themselves, so they can truthfully say they have no blood on their hands. This provides the necessary opportunity for the Atreides to escape.

The Bene Gesserit’s ability to Truthsay is thus a significant ability because it allows women to both determine whether someone is telling the truth, but it also affects how others make decisions knowing that they may be accountable in the future. Without any need for external equipment, these women are trained to be able to act as lie detectors and can enhance this ability and even become an official Truthsayer once a Reverend Mother. Along with their ability to use the powerful Voice, the Bene Gesserit show an extraordinary mastery of language and communication.

References:

[1] O’Reilly, Timothy. Frank Herbert. 1981.

[2] Herbert, Frank. Dune. 1965. Reprint Berkley Books, 1984. Pages 7-8, 58, 65, 151, 165-166, 169, 280, 531-532.

[3] “Tone.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

[4] “Timbre.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

[5] “Pitch.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

[6] Bunn, Geoffrey C. The Truth Machine : A Social History of the Lie Detector. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. Pages 2, 5, 75, 92-93, 117-118.

[7] “Wonder Woman.” Britannica.

Image Credits: